[Click any image to embiggen.] The forecast for the day called for rain, and left little room for doubt. I packed a rain jacket and rain pants (in the event of sideways-driven torrents). I packed an umbrella in case the rain remained vertical. I also covered exposed skin with sunscreen and packed a floppy hat in case the forecast was defied by reality. I wore heavy-weather shoes and thick wool socks. I packed a fleece as the forecast high was in the upper 50s. I knew I was going to be in the elements for the day. I wasn't go to bail no matter what. And I didn't want to be too uncomfortable.

[Click any image to embiggen.] The forecast for the day called for rain, and left little room for doubt. I packed a rain jacket and rain pants (in the event of sideways-driven torrents). I packed an umbrella in case the rain remained vertical. I also covered exposed skin with sunscreen and packed a floppy hat in case the forecast was defied by reality. I wore heavy-weather shoes and thick wool socks. I packed a fleece as the forecast high was in the upper 50s. I knew I was going to be in the elements for the day. I wasn't go to bail no matter what. And I didn't want to be too uncomfortable.

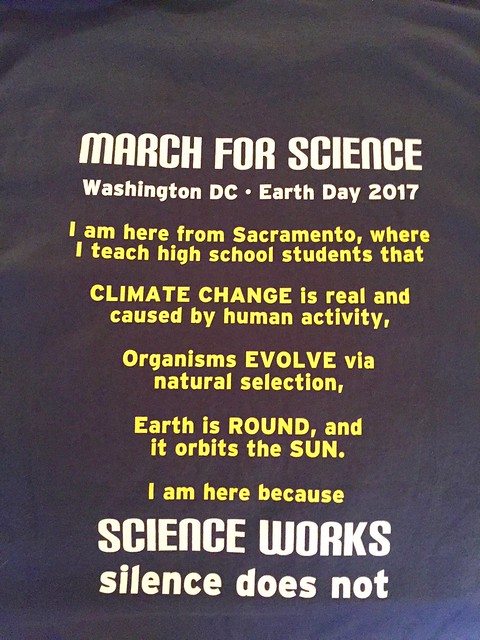

But in the morning, the weather was still fairly mellow, so I was able to expose my custom T-shirt.

I walked the mile and a half from my hotel to Pershing Park, where I was told representatives of the AAPT would be found. DC bustles on weekdays, but can be a ghost town early on a Saturday morning. I grabbed some breakfast at a bakery/cafe that was doing a brisk business with science marchers.

I found some familiar faces (Dan Brown and Rebecca Vierra) at Pershing Park; AAPT Director, Beth Cunningham quickly joined, as did some Society of Physics Students (SPS) enthusiasts. A retired chemistry instructor showed up in his rainbow tie-dyed lab coat, so I hauled mine out of my pack and matched his look. We socialized and snapped pics for a while before making our way to the rally at the Washington Monument.

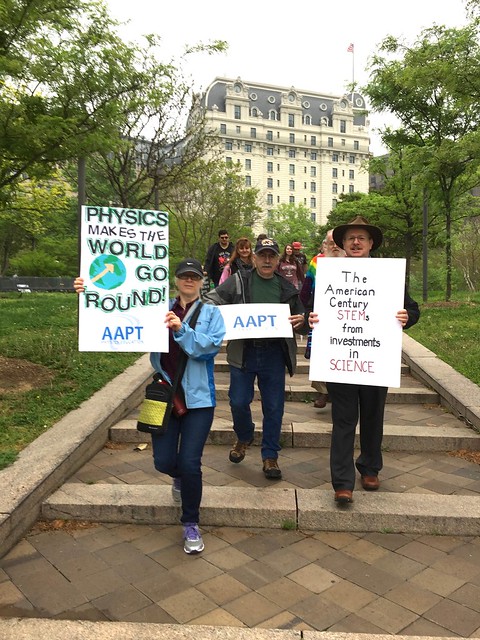

We knew we were headed in the right direction as we followed these two brainiacs.

We knew we were headed in the right direction as we followed these two brainiacs.

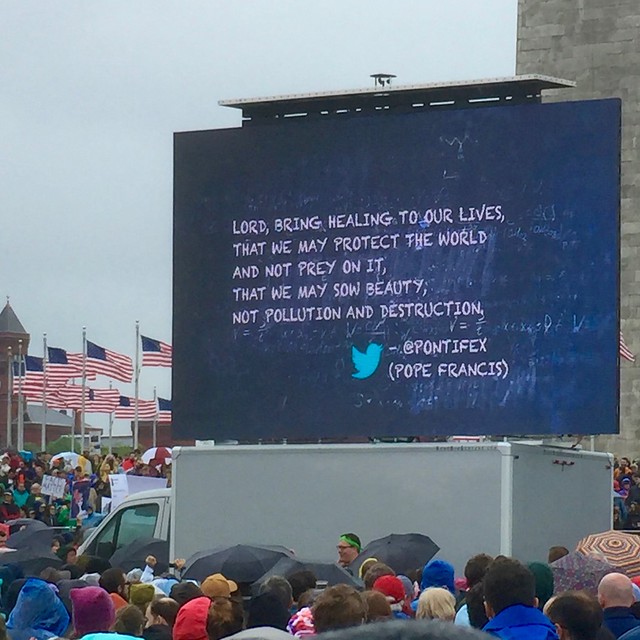

We settled in some distance from the main stage, but with a nice view of a massive screen (atop a truck).

At 10 o'clock, the program began. Veritasium's Derek Muller, Cara Santa Maria, and The Roots' Questlove acted as masters of ceremony. A precipitous mist turned into sprinkles as the program continued. The rainbow lab coat was stowed, and my rain jacket was deployed.

Speakers, music performances, and short films ensued. The rain picked up. It continued in waves. When it got heavy enough, my maize & blue Michigan umbrella was raised. Umbrellas were ubiquitous throughout the crowd. But you feel bad when packed this tight while using one. It blocks views and sheds water on your neighbors.

Four hours of rallying would have to pass before the march was to proceed. Scientists were celebrated, a call and response of "I say 'public' you say 'health'" was launched.

The rain never really stopped. When the wind reached a certain persistence, I undertook a pit-crew donning of my fleece between my t-shirt and the rain jacket. Had it not been such a tight pack where I was, I would have tried to put on my rain pants over the quick-drying trail pants I was wearing.

Near the end, we got a call to action from Bill Nye, himself.

And an Earth Day tweet from... not Donald J. Trump, but from Pope Francis.

Then it was off to the march. We slowly cattle-herded our way out of the secured Washington Monument grounds to Constitution Avenue and marched to the US Capitol.

From time to time, an enthusiastic roar would make its way through the marchers. And there were chants.

"Show me what a scientist looks like : THIS IS WHAT A SCIENTIST LOOKS LIKE!"

"Science--not hate--makes America great!"

The sprit was great and the energy was positive. The signs were very clever and were all spelled correctly. Hbar vs. FUBAR, Show us your taxa!"

The sprit was great and the energy was positive. The signs were very clever and were all spelled correctly. Hbar vs. FUBAR, Show us your taxa!"I stopped for a requisite US Capitol selfie.

At march's end, marchers laid down their signs along the walkway and fence leading to the Capitol: the impromptu sign graveyard blossomed and grew as more and more marchers finish the route. The rain had taken a toll on most of the signs, and the wind added entropy to the otherwise carefully placed placards.

At march's end, marchers laid down their signs along the walkway and fence leading to the Capitol: the impromptu sign graveyard blossomed and grew as more and more marchers finish the route. The rain had taken a toll on most of the signs, and the wind added entropy to the otherwise carefully placed placards.Snake Oil Trump will haunt my dreams for nights to come.

At the end of the day, there was no way to navigate around the reality that science is under attack in the US from the Republicans who hold the presidency and majorities in the Senate and House of Representatives. It is likely that they will do significant damage to science and the environment as rapidly as they can. It is unlikely that they will change. We cannot nourish a hope that the attack will relent while the GOP maintains unbridled governmental power.

If scientist hope to get work done in the lab, they will need to get work done at the ballot box first.

I'm glad I was able to be in DC for the March on Science. I have more photos in my Flickr album and more videos on my YouTube channel.

March for Science Photos: